Half of the country’s unsheltered population resides in California, according to a U.S. Housing and Urban Development report.

In December 2022, the state had 171,521 people experiencing homelessness.

“This is more than nine times the number of unsheltered people in the state with the next highest number, Washington,” the December 2022 report stated. “In the 2022 point-in-time count, Washington reported 12,668 people or just 6 percent of the national total of people in unsheltered locations.”

Between 2020 and 2022 California also experienced a 6.2 percent increase in its homeless population—the largest increase in the country. To help combat this, the state increased the number of housing units that local jurisdictions are required to develop with the help of their housing elements, a state-required process that looks at housing needs every eight years, said Santa Barbara County Director of Planning and Development Lisa Plowman.

Before any jurisdiction begins updates, California looks at census information, population changes, and affordability issues to determine its needs, Plowman said. After that, counties and cities will have to look at what land is available for development and what land could be rezoned in order to meet those numbers.

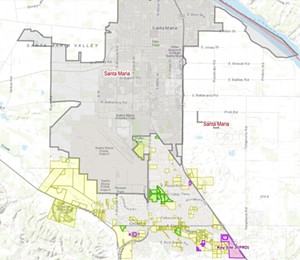

This cycle, Santa Barbara County will have to find areas that could develop 5,664 new units by 2031—with 1,522 in unincorporated North County and 4,142 in South County—a significant jump from 661 units required during the 2015-23 Housing Element. According to a 2020 progress report, the county hit most of its housing element goals but fell short in its low-income housing allocation with only 117 of the required 265 units.

“This cycle, our housing allocation was eight times higher than the last cycle. The state has been giving people high numbers because they believe the state is in a crisis,” Plowman said. “The state has grown intolerant of jurisdictions saying they’re planning for housing but not identifying sites to be redeveloped. They’re pushing greater numbers and passing laws every legislative session, making it easier to develop housing.”

Cities have to reach their own high numbers as well, with more 5,000 units allocated to Santa Maria and 8,000 to Santa Barbara.

Although many jurisdictions—including Santa Barbara County—are running late to meet their mid-February state deadlines for creating updated housing elements, Plowman said she thinks the state’s push is necessary to make it easier to live in Santa Barbara County, as well as anywhere else in the state.

“This is not a new problem, this is a decades-old problem. Right now just on the South Coast, less than 8 percent of renters are able to afford a median-priced house,” she said.

The median income for a family of four in Santa Barbara County is about $100,000, but the median home price is $670,000—but looking at South County alone, Plowman said, the average cost of a home is $1 million.

Home prices in North County are also on the rise, averaging about $700,000 in Orcutt and Los Alamos, with Santa Ynez reaching $1.3 million.

“Rent and mortgages have been climbing all over the country,” Plowman said. “Retention and recruitment is a huge problem in the county. A third of our employees live in another county.”

According to state standards, people are considered “housing burdened” if they are spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing, she said. In Santa Barbara County, people would have to earn $328,000 a year to not be housing burdened. Even renters would have to make $86,000 to afford a one-bedroom and almost $152,000 for a four-bedroom.

“There is definitely a problem. Only 20 percent of our population earns over $150,000,” Plowman said. “What’s happening is the housing prices have been climbing and incomes have been climbing, but not at the same rate. That’s been happening since the 1970s, 1980s, and it’s just continued to widen the gap.”

Now, the county has to figure out a way to meet the state’s demands and get housing built that works with surrounding communities, she said.

“There has not been one housing project that hasn’t been fought by the neighbors, but when they’re built, nine times out of 10 they blend in and they become an accepted part of the fabric,” Plowman said. “But change is hard.”

In public comment letters submitted to the county about the recently released 2023-31 draft housing element, residents said they don’t agree with development coming to their area.

“I am very disappointed that the county has targeted our valley for development, and the city of Carpinteria will feel the effects in the form of traffic, pollution, water use, sewage, and further squeezing of ag out of the valley,” Carpinteria residents Jon and Sue Lewis said. “The supervisors need to focus on putting development where it makes sense (i.e. Orcutt, Lompoc, Santa Maria) and not add to our issues on the South Coast.”

Part of the housing element’s goal is to address the jobs-housing imbalance. Santa Barbara County tends to have more jobs available in South County, but not enough housing available to meet the need. Currently, many residents have to commute from North County or other counties in order to get to their jobs on a daily basis, Plowman added.

“That has a big impact on the richness and diversity of your community; you have parents driving two-plus hours every day commuting,” she said. “We need to meet the needs of where the workers are.”

Orcutt resident Alicia King also submitted a public comment letter, expressing concern about the amount of resources available and a potential future loss of open space.

“I do understand we need housing, it’s a huge issue,” King said. “I’m hopeful the final housing element has a way to ensure adequate resources, schools, trails, parks, etc., can all find a way to exist together.”

Solvang resident Brandon Sparks-Gillis wrote to the county about his five-year-long, frustrating journey of trying to buy a home. He said that the housing element is not the answer to all of the county’s issues—including a lack of infrastructure in smaller jurisdictions and an increase in short-term rentals.

“This dynamic is devastating, not only to low-income county residents, whose rents are being artificially inflated upwards, but also to ‘middle class’ county residents who are now watching their rents soar and their dreams of home ownership disappear,” Sparks-Gillis said.

County residents have until March 1 at 5 p.m. to submit their comments. The county then has 10 days to review and consider the comments before submitting the element to the state for a first draft review, Planning and Development Director Plowman said.

“Our deadline is Feb. 15, and we are missing our deadline like I would say the majority of jurisdictions. In the Southern California region, there’s 196 jurisdictions and 191 of them have missed the deadline. It’s become quite cumbersome,” Plowman said.

Santa Barbara County has been working closely with the state Department of Housing and Community Development to ensure its draft housing element is as comprehensive as possible, she said.

The county is set to adopt that draft in late summer or early fall 2023 and is required to adopt proposed areas for rezoning 2024, Plowman said.

“The big picture is the state is losing patience and the state has determined we have a housing crisis and they want to see housing built, which is why our numbers are so big and there are consequences if [we] aren’t in compliance,” Plowman said.

“The state is pushing on us, but there is truth to the housing crisis, and we see it daily in our community.”

Reach Staff Writer Taylor O’Connor at [email protected].