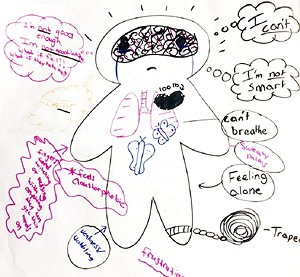

"I'm not smart." "I'm not good enough." "I can't."

Those are the sentences written in boldly drawn thought bubbles stemming from a distressed stick figure's mind. His brain inside is clouded and chaotic, his stomach is filled with butterflies, and his heart is heavy and black.

The drawing is one student's idea of what anxiety looks like, and its key characteristics are repeated in similar drawings by students throughout San Luis Obispo County, students who participated in Transitions-Mental Health Association's new suicide prevention training program.

Transitions-Mental Health, a nonprofit that provides mental health services to families across the Central Coast, launched the program last year in San Luis Obispo with a $100,000 grant from the Gertrude and Leonard Fairbanks Foundation. The goal? To give kids and educators tools to better help students struggling with mental illness.

It was incredibly successful, according to Transitions Development Director Michael Kaplan, who said the nonprofit recently won another $65,000 grant to continue the program.

And this time, it's coming to the Santa Maria Joint Union High School District.

"I quickly realized there was a real need and enthusiasm for this program [in Santa Maria] so we made the decision to start providing it," Kaplan said, adding that Transitions will start the program at Santa Maria's high schools in October.

Although Kaplan said he's still waiting to hear back on a federal grant that would help fund the program's expansion to Northern Santa Barbara County, local administrators wanted so badly to participate, "I was not going to tell them no."

Through the program's two adult training sessions, faculty, counselors, and administrators learn how to spot kids with unmet mental health needs and connect them with necessary resources. Both sessions meet student suicide prevention guidelines mandated by the state.

Teachers, Kaplan said, are often unintentionally placed on the front lines of the battle against childhood mental illness. Educators don't need to become psychiatrists, he said, but they should know simple ways to identify and help struggling students.

"I think [the trainings] are important right now because the topic has come out of the shadows," Kaplan said. "People are ready to talk about mental health and mental illness and not treat it like a secret. But there is a lot of misinformation out there."

Roughly three-quarters of people with mental illnesses experience their first symptoms before age 24, according to the 2016 California Health Report. Half become mentally ill by age 14.

Santa Maria's schools face similar challenges.

Each year, the Santa Barbara County Department of Behavioral Wellness serves more than 3,000 children who are severely emotionally disturbed, according to the county's 2017 Children's Scorecard. Although the county entirely lacks youth psychiatric crisis beds and facilities, youth inpatient admissions through Behavioral Wellness rose from 45 in 2010 to 100 in 2015.

The death of Righetti High School student Kiya McBride, who killed herself in November 2017, is also still fresh in the minds of many community members.

With 23 school counselors, three crisis intervention consultants, four school community liaisons, seven school psychologists, and additional mental health resources provided by several organizations, the Santa Maria Joint Union High School District is working hard to keep its students healthy. But John Davis, assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction, said it's vital for teachers and students to know the warning signs of mental illness and suicide.

"In that sense these trainings could literally be a 'lifesaver,'" Davis wrote in a statement to the Sun, "and certainly a worthwhile endeavor for our district."

When it comes to training students, Amy Waddle likes to keep it real, relatable, and fun.

Waddle, a professional public speaker who partners with Transitions to train students, said she teaches kids how to identify struggling friends, how to reach out, and ways to be encouraging and get help.

It's nothing new and it's fairly simple subject matter, but Waddle said Transitions' curriculum makes it easy for students to feel connected and supported.

In the exercise where students are asked to draw what anxiety feels like to them, Waddle said that most of the drawings turn out fairly similar. And as kids look around at the other drawings, they feel less alone.

"It's sad but it's also kind of beautiful," Waddle said. "They don't know it yet but they're just like everybody else."

Staff Writer Kasey Bubnash writes School Scene each week. Information can be sent to the Sun via mail, fax, or email at [email protected].