There’s been plenty of speculation about whether or not this winter will bring big storms along with lots and lots of water. Forecasters won’t say for certain, but there is one thing we do know: water, the wet stuff of life on earth, is currently in short supply.

It’s hard to imagine a storm that could bring much, in fact, when water has been scarce for so long. It’s a rare thing to see water running in the streets or falling from the sky these days. It’s so rare that California set aside $30 million in rebates to entice homeowners to replace their toilets and rip out their lawns in order to save the state’s dwindling water supply.

Water is evaporating all over the state. Cachuma Lake has dropped to 17 percent of its capacity, according to reservoir measurements taken by the county. Twitchell Reservoir, with just 115 acre feet of water left, is sitting at 1 percent capacity.

John Lindsey, meteorologist with PG&E, confirmed what many could already tell you: that the drought is not just bad—it’s historically bad. That’s according to rainfall records in California, which Lindsey said go back almost 150 years.

“According to those records, we’ve never seen four straight years of drought. In that matter, it’s unprecedented,” he said.

Warm weather phenomena amplify those dry conditions. On the Central Coast, we’ve had more Santa Lucia easterly winds than usual, Lindsey said. They sweep in from the mountains and push the marine layer out to the sea. That means less fog and high clouds, which in turn means higher temperatures.

“The warmer temperatures we’ve had and the warmer air mass, the faster everything will dry out,” Lindsey said.

That has created a disruption to more than just lawns and landscaping.

Marine mammals are washing up emaciated and dead because their food sources have moved up north, according to the Department of Fish and Wildlife. Other marine animals, like tuna, and their southerly predators—hammerhead sharks, rarely seen off this part of the coast—are following the warming sea northward as well.

This is California in 2015: badly dried out, with both land and ocean setting heat records. This winter, however, a periodic weather cycle may deliver some relief. It’s called El Niño, after the Christ child, because it often falls around Christmas.

El Niño, under the right conditions, brings rain to Southern California and dries out the Pacific Northwest. It happens when a stripe of warm water in the Pacific meets a mass of warm air. And this year, as the temperature of the Pacific Ocean soars to the warmest that scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have observed since 1908, it looks like that warm air-water meeting just might happen in a big way.

What will an El Niño bring to the Central Coast?

Weather forecasters won’t confirm whether an El Niño will arrive, but Lindsey, the PG&E meteorologist, predicts a strong one.

“For our area, weak and moderate El Niños don’t have much forcing,” he explained. A strong El Niño, however, could raise rainfall to 140 percent of normal

The ocean temperature is right, according to Lindsey; the blob of warm seawater off of the Pacific Northwest has dissipated, as have the fears that it will draw off the jet stream and keep Southern California dry. And the ridiculously resilient ridge of high-pressure air, long responsible for shunting storms away from California, has “weakened tremendously.”

For Santa Barbara County, Colorado University research scientist Phil Klotzbatch predicts that a stronger-than-normal jetstream will bring extra rain. His question for California, starved of water as it is, is how far north that jetstream will extend: the uncertainty is whether the Bay Area will get more rain.

Much of the water the state gets from rain falls in Northern California before it’s transported south by the State Water Project. Most of us are drinking at least some of that water from Northern California when we turn on our taps, so the amount of rainfall that San Francisco gets matters more to Santa Barbara County than you might think.

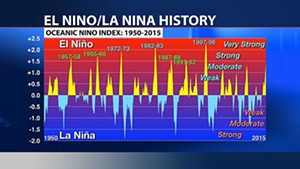

Klotzbatch sent the Sun charts in which he organized past events by intensity and rainfall. “When I sort El Niños by intensity (since 1950), the four strongest El Niños all brought heavy rain to San Francisco, while weak to moderate El Niños didn’t show much of a relationship,” he wrote in that email. “This El Niño looks to be one of the strongest that we’ve had since 1950, and consequently, that lends increased confidence in an above-average precipitation forecast for the Bay Area.”

Dave Hovde, meteorologist with KSBY, said that this El Niño tracks “almost exactly” with the 1997-1998 El Niño, which was one of the strongest on record. “There’s a lot of reason to be optimistic,” he said.

“El Niño is still on track,” echoed Bob Henson, meteorologist and blogger at Weather Underground. “It’s happening.” The event, he said, depends on both the ocean and the air. In recent years, the conditions in the ocean were right for El Niño but the air wasn’t following suit. This year, both are in line for a strong event.

“When you move all that warm water and warm air thousands of miles, the atmosphere has to rearrange,” Henson said. “Winter-like storm systems are more likely to head into Southern California, because of all that warm water and air. You have more moisture to fuel those storms when they arrive.”

The snowpack, he cautioned, might not be recharged—the storms that make it to the Sierra Nevada might be too warm. Henson, like any good forecaster, cautioned against certainty, and pointed out that climate change is making the business of predicting the weather harder than it’s ever been.

“In a changing climate, it makes it even harder to look back through the past 100 years and have total confidence in what’s going to happen in our future,” he said.

Mike Halpert, deputy director with NOAA’s climate prediction center in Maryland, cautioned that while El Niño will ease drought conditions, it likely won’t end the drought—and getting that amount of rain could cause serious damage.

“That’s going to take a lot of rain—maybe more rain than you’d like to see in a rainy season,” he said. “You’d need twice the normal amount of rainfall. That’s not been observed, although a few years had been close. But, from a practical standpoint if you have that much rain, it’s going to result in a lot of flooding and landslides in certain areas.” He cautioned that the drought, which has hardened the ground, and wild fires, which have stripped away vegetation, could make those adverse effects worse.

“We don’t get to pick and choose,” he said. “What Mother Nature gives you guys, you’d have to deal with.”

Living on a floodplain

Should an El Niño take place, it could spell trouble for Santa Maria. At worst it could mirror or surpass the devastating effects of the 1997-1998 El Niño.

That event saw $550 million in damage to California, according to Golden Gate Consulting Services. California was deluged with water, battered with 20-foot waves, and blasted with 80 mph winds. January was wet that year; February was wetter, with a record 11.59 inches of rain in Santa Maria, according to the Western Regional Climate Center. County officials say that during that winter, Santa Barbara County soaked up 40 inches of rain—more than double the county average, which is around 18 inches per year.

Statewide, 17 people died. Two of the fallen were CHP officers Britt Irvine and Rick Stovall. Travelling on the stretch of Highway 166 east of the Santa Maria River in heavy fog on Feb. 14, they drove into a gaping hole churning with water, mud, rocks, and asphalt.

The Cuyama River, swollen with rainfall, had uprooted protective boulders and swallowed up the highway. It flowed with such force that the asphalt tarmac and riprap beneath were peeled away like wet paper. Another casualty of the storms, according to news reports of the day, was Michael Bennet Tye of Nipomo, who went missing during the washout and still hasn’t been found.

Short of El Niño, heavy rainfall alone can take its toll on the city of Santa Maria, which sits on a floodplain.

“It is possible for Santa Maria to get X amount of water in a short of time,” said Mark van de Kamp, public information officer with the city. “People are like, ‘Oh, nothing ever happens.’ You’d be surprised.”

For thousands of years, the shifting course of the Santa Maria River has deposited sand onto that plain; it soaks up water with relative ease, but not so much when there is substantial rainfall. That’s why several parks in Santa Maria—notably Minami, Jim May, and Simas—are deliberately sunken into the ground. They’re big retention basins, basically, designed for holding water. When it rains, they fill up.

“Everything under the city is sand,” van de Kamp said. “Depending on the rainfall, we can see the water and in one day, it can be gone.”

Another way of controlling potential flooding is the levee that stands between the bed of the Santa Maria River and the city. The 50-year-old levee landed on a 2008 Army Corps of Engineers list of national levees in danger of failing. Ultimately the corps, city, and county pulled together $40 million to strengthen the section of the levee that runs from Blosser Road to the Bradley Canyon spur. The work was completed in May of last year. Tom Fayram, the director of Public Works for Santa Barbara County, is confident that the levee is now good to withstand 150,000 cubic feet of water flowing past per second.

“That’s a lot of water,” he said. “That’s the highest volume flow that we have anywhere in the county.”

Cognizant of the city’s floodplain status, when it rains, van de Kamp said city and county employees go out and clear away obstacles such as leaves and branches that could clog drains. “In some of the more flood prone areas, we’ll do drive-bys to speak with residents,” he said.

That’s one way the city encourages residents to be prepared for and aware of the dangers of flooding. The city doesn’t provide sandbags, although it will provide sand. Officials emphasize that residents should call and prepare before their house floods, not after, and that buying flood insurance could be a good idea.

That’s because floods happen—in low lying areas or in areas where drains have clogged—despite the best efforts of the government and the public. The intersection of Blosser and Taylor streets, van de Kamp said, is sometimes prone to flooding. The corner of Blosser and Donovan is another area where flooding’s been seen in the past. “There’s some occasions where we’ve had some street flooding where the drains are just overloaded,” he said.

In December of 2014, Santa Maria was battered by thunderstorms, and the living quarters of Fire Station No. 1, on Pine and Cook streets, flooded. “That was unusual,” van de Kamp said. “There was no place for the water to go.”

Leaves and muck had clogged nearby drains, and the station flooded quickly. Despite the flooding, firemen responded to 41 different calls; Recreation and Parks spent all night responding to 28 reports of fallen tree branches; county fire took care of 33 calls for fallen power lines; and Black Road was temporarily impassable. Thousands were left without power, and police cars and fire trucks were damaged while trying to get through the water to people calling for help.

Roy Dugger, an emergency services specialist with the city of Santa Maria, emphasized that the public can’t lean on the fire department or police in an event like this. Those agencies, he said, don’t have enough staff to do everything. They need buy-in and preparation from citizens and residents to make it through.

Ultimately, planning will help residents weather an El Niño but it won’t change the weather.

He added that preparation only gets you so far. “No matter how much planning you put in in advance, there’s no way of stopping certain events,” he said.

Staff Writer Sean McNulty can be reached at [email protected].