It’s time for a breather. The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians and Santa Barbara County’s ad hoc subcommittee are taking a break from their monthly meetings to step back, work out some kinks, and plan out how to move forward.

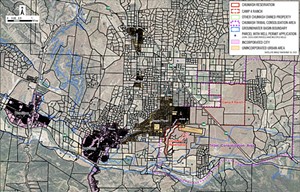

The meetings began in September 2015, after Congress told the county to sit down with the Chumash and work out their differences. The county’s ad hoc subcommittee and tribal representatives decided early on that their discussions would focus on Camp 4, a 1,400-acre site in the Santa Ynez Valley that the Chumash said was necessary for housing.

The Chumash want to take Camp 4 into federal trust, but first the tribe needs to reach agreements with the county on issues including waivers of sovereign immunity, water usage, gaming terms, and reimbursement for lost property tax—all of which have been argued, and some resolved, at the county-tribe meetings.

After seven discussions, the subcommittee presented a report providing an overview of the meetings’ progress at the Board of Supervisors’ March 15 meeting. The board voted to hit pause on county-tribe discussions for five months or so, during which time the parties’ legal representatives will iron out their most stalemated issue: sovereign immunity.

The Chumash had agreed to waive its sovereign immunity, per the county’s request—but when the tribe asked the same of the county, negotiations stalled. The subcommittee worried that if the county waived its sovereign immunity, the individual supervisors would become vulnerable, according to subcommittee member and 3rd District Supervisor Doreen Farr.

“It looked hopeful that their counsel and our counsel were coming to an agreement on acceptable language, but then that seemed to backtrack on the tribe’s part,” Farr told the Sun. “Of all the issues, that was the most concerning to the Board of Supervisors.”

The board told both parties’ legal representatives to work out the language for the sovereign immunity waivers. The meetings should resume in August or September, after the sovereign-immunity issue is settled.

Interim Tribal Chairman Kenneth Kahn said he was disappointed by the supervisors’ decision to suspend the county-tribe discussions.

“I would have preferred the meetings to continue,” Kahn told the Sun. “We felt like we were making progress. Even though there were contentious items, we were closing the gap. But the county brought these communications to a halt.”

Kahn called the hiatus “another setback in trust and willingness to work together.”

For the Chumash, the issue of trust isn’t new. Former Tribal Chairman Vincent Armenta expressed the same wary sentiment to the Board of Supervisors at its March 15 meeting.

Armenta’s concern was with the Mooney-Escobar property, two parcels of land the Chumash had been vying to take into trust—until county supervisors voted to block it in closed session. Armenta said the county used the ad hoc subcommittee discussions to inform its closed-session vote on Mooney-Escobar, which he thought was unethical.

Armenta said such behavior was like the county inviting the Chumash to the watering hole, then “shooting them in the back when they walk away.”

“If we’re supposed to be having discussions for the purpose of discussion, to see if we can come up with an agreement, why are we using those discussions against the tribe?” Armenta asked the supervisors. “We obviously can’t continue conversations if every time we say something in negotiations, you take them and use them against us. It’s disturbing. It’s crazy. And it’s been done time and time again.”

Two days later, Armenta announced his resignation. After 17 years of serving as tribal chairman, he is now moving to New York to pursue an education at the Culinary Institute of America—a career change Armenta insisted was “absolutely not” related to the tribe’s tensions with the county.

“Nothing really prompted my decision to resign,” Armenta told the Sun. “I’ve been doing this for 17 years. I’m very comfortable with the position the tribe is in. I feel comfortable that the next elected tribal chairman will continue on the same path.”

Kahn said the next chairman election will take place April 12, but the winner most likely won’t be announced until early May. He added that despite the curious timing of Armenta’s announcement, the chairman had been planning to resign for a while.

“The county ad hoc subcommittee meetings had absolutely no effect on his decision,” Kahn said. “It was something totally separate, and something that he’s been thinking about and contemplating for quite some time.”

Farr said she and 4th District Supervisor Peter Adam, who also serves on the ad hoc subcommittee, had no prior knowledge of Armenta’s resignation.

Despite Armenta’s and Kahn’s reservations about pausing the meetings, Farr said the county and tribe needed to take a break and start again from a clean slate later on. Their discussions’ framework had become muddled, she said.

For example, though the county and tribe intended to restrict their negotiations to Camp 4, the tribe had recently expanded meeting discussions to include other properties. Farr said the county and tribe would have to clarify their negotiation parameters before resuming discussions.

She was equally concerned with gaming terms for the land: Though the Chumash had agreed to abide by the House of Representatives Bill 1157, which would prohibit gaming on Camp 4, Farr wanted the same commitment from the tribe on a county level.

“They had committed that to both the BIA [Bureau of Indian Affairs] and to Congress, so we were really scratching our heads over why it would be so difficult for them to give us that statement,” she said.

Kahn told the Sun that federal restrictions should be enough to assure the county.

“For us it would be repetitive. We have and will always be governed by federal law,” he said. “It’s a serious law.”

Despite these points of contention, both Farr and Kahn said they thought the county-tribe discussions have been effective.

“It was a historic first to have open meetings between the tribe to discuss these issues of mutual concern,” Farr said. “It just seemed really important to me that whatever discussions we had were out in public and transparent and taped so anyone who’s interested could go back and watch them.”

She said the meetings provided a structure for tracking progress and keeping records of how each party had compromised on every issue.

“It’s been a really good process, an important process, and I think the transparency has been a huge piece of it,” Farr said. “Hopefully we’ll get the language worked out and come end of August or September we’ll ramp back up again.”

Kahn agreed, saying the community depends on a good working relationship between the county and tribe.

“Our youth, they’re in the same schools,” he said. “We’re all in the same coffee houses and working in the same businesses. We’re a collective community, tribal and non-tribal, so it’s very important for us to come to an agreement.”

Staff Writer Brenna Swanston can be reached at [email protected].