Incarcerated people are among those with the least agency in the United States. Some argue that this is a key part of serving justice. The punishment—confinement and everything else that comes with it—fits the crime. Others say prisoners should have more rights, advocating for felon enfranchisement or labor compensation.

“Inmates have a Ph.D. in what Californians are learning: Namely, how to sit at the edge of your bed and do nothing,” Charles Carbone, a prison reform lawyer, told the Sun. “‘Quarantine’ is not a new word for the inmate population.”

But amid this pandemic, Carbone said, it’s worse.

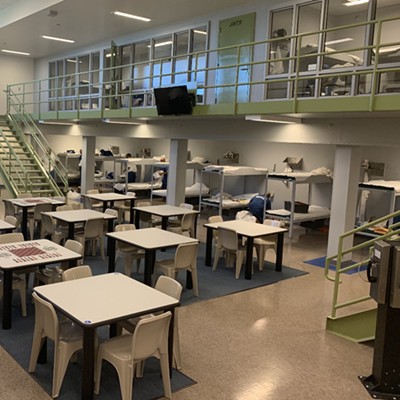

“It is a public health crisis on steroids because of the easy communicability of the disease inside a prison setting, the existing lack of hygiene in the prison system that will also allow the disease to run, and then the constant and close interaction that that entire inmate population by necessity has to have with staff,” he said.

Some Central Coast prisons are already experiencing the worst of it: For the first weeks of April, the Lompoc penitentiary had the highest infection rate among all Federal Bureau of Prisons facilities in the nation. As of April 20, it had 54 infected prisoners—only two prisons had more positive cases—and the first inmate death from the virus was reported on April 18. The California Men’s Colony, a state facility operated under the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), trails a few weeks behind the penitentiary’s curve at one COVID-19 case so far.

“They need to learn from what’s happening at Lompoc,” U.S. Rep. Salud Carbajal (D-Santa Barbara) told the Sun. “Perhaps they can learn of the impact and the problems we’re having and see how that might impact the Men’s Colony.”

The Lompoc prison’s leadership is now starting to work toward the construction of a field hospital to house the inmates who need medical attention. Initially, Carbajal said, the Bureau of Prisons told him that it would take four to six weeks to get the field hospital up and running.

“I have been told by other stakeholders and public health officials at the county that four to six weeks is too late,” Carbajal said. “This needs to happen right away.”

In response to the bureau’s original estimation, Carbajal decided to pen a letter alongside California Democratic Sens. Kamala Harris and Dianne Feinstein demanding that the prison leadership build the field hospital as expeditiously as possible, and also that they fill medical and prison staffing levels, which as of the April 14 letter, were at 68 percent and 80 percent, respectively.

“I am encouraged that I have heard through different sources that the Bureau of Prisons is looking at expediting that effort,” Carbajal said. “I’ll believe it when I see it.”

A few days later on April 21, the same Congress members sent a second letter to the Bureau of Prisons “to continue stressing the need for the BOP to move with urgency in establishing this facility with the necessary staff and equipment—including ventilators,” they wrote. The second letter also addressed reports of an inmate from the facility being released with COVID-19 symptoms and not receiving treatment prior to his release, as well as insufficient personal protective equipment for staff.

Meanwhile, the Santa Barbara County Department of Public Health confirmed the county jail’s first case in an April 17 press conference. Over the last few weeks, the jail has made efforts to expand early releases for its inmates, bringing the jail’s population down to the lowest it’s been since the 1970s. But for the federal prison system, release is not a simple process.

“Currently, there is no parole in the federal system,” Scott Taylor, a bureau spokesperson, told the Sun in an email. “Only a few inmates remain who are parole eligible. For the federal system, we are using home confinement as a means of transferring inmates to the community.”

Taylor said that the bureau “has begun immediately reviewing all inmates who have COVID-19 risk factors,” and of those individuals, determining “which inmates are suitable for home confinement.”

Unlike the federal prison system, the state-run CDCR has thousands of inmates working toward parole. But their release is contingent on gaining enough “rehabilitative achievement credits” in programs that are largely stalled in response to COVID-19.

“All of the rehabilitative programs, all of the vocational programs, all of the educational programs, all programs that get inmates together, … in CDCR all of those programs are offline right now,” prison reform lawyer Carbone said. “You have 40,000 lifers in the state of California whose paroled release is largely dependent upon them participating in rehabilitative programming.”

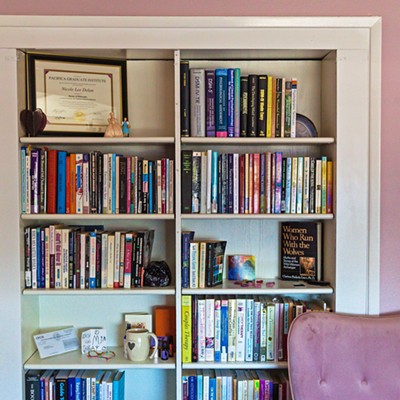

Dana Simas, the CDCR’s press secretary, wrote in an email to the Sun that “the Office of Correctional Education is working with institution principals, library staff, and teachers to provide in-cell assignments where possible in order for students to continue their studies, legal library access, and educational credit-earning opportunities.”

However, Simas confirmed that because state law requires that rehabilitative achievement credits be earned in the presence of an instructor, and because instructors are currently not allowed inside the prison, inmates will not be able to earn rehabilitative achievement credits while visitation remains suspended—a reality Carbone expressed concern about.

The CDCR is making efforts to compensate for COVID-19 related visitation suspensions by giving the adult incarcerated population three days of free phone calls each week through the end of April, with no limit on the number of calls.

Similarly, the Bureau of Prisons “increased monthly telephone minutes for all inmates from 300 to 500, in recognition of how important it is for families to stay in touch during this time,” Taylor wrote. “Telephone calls are free to inmates for the duration of this emergency.”

Carbone said that prisons will ultimately have to find a balance between the advantages and disadvantages that congregated living situations have on the spread of the virus.

“It’s a competition between the ability to segregate and the ability to control movement on the plus side of the prison system, against the proximity and ease of communicability on the negative side,” he said.

As Rep. Carbajal pointed out, the Lompoc prison is critically understaffed, and an understaffed facility cannot begin to address the level of retooling within the prison system that COVID-19 requires. That’s why Carbajal said he is asking leadership within the bureau to increase staffing and other gaps at the Lompoc penitentiary, as well as urging the Men’s Colony to learn from Lompoc’s mistakes.

“Some institutions certainly have been caught flat-footed. Everybody’s trying to do their best to adjust and adapt to this fluid circumstance,” Carbajal said. “But it certainly has identified weaknesses and lack of systems and plans that need to be enhanced and modified for the future.”

Reach Staff Writer Malea Martin at [email protected].