Wisps of wind whip soft sand up from a private road that began in and meanders to what could rightfully be labeled the middle of nowhere.

Low-slung buildings creep into view between the squat, stocky vegetation that covers the desert hills outside of Cuyama. Goats snack on shrubs, and a couple of white sheep dogs bound next to the car, barking. A trail takes visitors from the parking area to an office constructed of straw bales coated in clay soil, sand, and straw.

"Welcome to Quail Springs," a sign says.

Soft, weathered earthen walls the same color as the hillsides line the planters that border an outdoor common space. Chickens cluck away in the large coop below, and Creedence Clearwater Revival wonders "Who'll Stop the Rain?" through the walls of a yurt that houses a kitchen.

"Welcome to the farm," Quail Springs Executive Director Janice Setser says.

This experiment in sustainable living is part educational experience, part trial and error, part social exercise. The life on this 450 acres in California's high desert is complex with many layers, Setser says. And it's extreme, with temperature swings that come with snow, ice, and blistering heat from winter to summer. Containing a farm, a greenhouse, composting toilets, yurts, naturally crafted buildings, 11 staff members, a handful of interns who come and go, and lots of outdoor space, permaculture is at the heart of everything that's done around here.

"[Society has] separated things out so specific and specialized," Setser says. "And permaculture is just putting it all back together again."

The goal is to close as many loops in the system as possible, to live off the land and regenerate it at the same time, to meet basic needs from the earth at your feet in a way that can last. It's a relationship with the wilderness and the community tending the land—a way of remembering something that humans seem to have forgotten.

She admits, though, that the living experiment in sustainability is difficult and imperfect. But, Setser says, the Quail Springs community is leaning into it.

Walking past a pile of dried rubble laced with straw, she points out that these are earthen walls that a couple of Cal Poly students and a professor performed earthquake testing on over the last several months. The 12-inch thick walls were built out of a material called cob, a mixture of soil, sand, and straw. After the testing was done, the walls were knocked over on purpose, she adds.

Cob, which is one of the primary building materials on this property, isn't part of California's building codes. But Quail Springs is working to change that and so are others who believe that cob is a cheaper, more energy-efficient and sustainable, and less toxic way of building. Quail Springs Natural Building Director Sasha Rabin said the information that's out there about cob building is anecdotal, and modern codes, architects, and engineers need numbers.

"In order for people to build in urban areas in seismically active zones, we need engineering numbers," Rabin said. "We need engineers to be able to stamp our plans to say, yes, this is safe."

In 2018, Santa Clara University students performed the first ever full-scale wall tests on four cob walls, some of which were reinforced with different materials, including rebar and a wire mesh. Although straw gives cob tensile strength, Rabin said, other ways of reinforcing walls could be key to incorporate into a potential building code for the state. The partnership between Cal Poly and Quail Springs will add to that research. With four similarly structured walls that underwent six seismic tests, Rabin said the collaboration multiplies the amount of earthquake data that's out there on earthen walls. The results of those tests aren't ready yet, but Rabin said she believes they went well.

Next up on the list of tests for the earthen walls is fire. She said that Quail Springs is looking for funding to build a cob wall at a fire testing facility.

"Normally, all of these tests are being done by the manufacturing companies that are hoping to profit off the materials they're selling," Rabin said. "Most of the materials that we use just come from on-site: We just dig them up."

Gathered on-site

Dirt rains onto a tarp as Chad Franco trims the last layer of cob he applied. Using a hand saw, he carves out the excess around the edges so this layer is flush with the previous one.

The gigantic white walls of the new BMW dealership on Calle Joaquin loom behind him, as does the chatter of auto service professionals. A fence and less than 100 feet separate that property from this one, which belongs to City Farm SLO.

On the plot of land that Teresa Lees rents from City Farm for the Our Global Family Garden, Franco is building a cob structure that will eventually become a children's playhouse. Lees designed her garden with each of the continents in mind, and this structure is part of the Africa space.

"I was in Africa, and we lived in buildings like that," she says. "Instead of being a white woman visiting the Third World ... [I thought] I'm going to bring back what I learned there to the First World."

With a degree in international agriculture from UC Davis and an agricultural teaching credential from Cal Poly, Lees worked in small villages, connecting with people who lived off the land, and doing the same herself. That connection, and the world's interconnection, is what Our Global Family Garden is all about. It's a teaching space dedicated to showcasing permaculture, compassion, connection with the land, and the diversity of what can be grown around the world.

Next to the fence, a smaller hole than you would expect is evidence of the clay soil that was incorporated into the structure. Depending on how much clay the dirt holds, the cob mixture of soil, sand, and straw is unique to each building site. It has to be the perfect consistency. After making some test bricks, Franco says, they dropped them to see which ones held up the best. In this case, the mixture was 25 percent clay soil and 75 percent decomposed granite before the water and straw were added.

And it was all mixed by feet. Some of those feet belonged to kids who attended two weekends of cob workshops at City Farm SLO in November.

"It's been a long journey. In the future, I probably won't start a project in November," Franco says, referring to all of the rain San Luis Obispo weathered over the winter.

The structure has spent a lot of time under the cover of a blue tarp, waiting for dry days—not just for the cob itself, which needs dry weather to cure, but to schedule workshops. Building cob, because it's so labor intensive, is really a team activity.

This project is a labor of love for Franco, though, who has been cobbing since he took a six-month permaculture workshop at UC Santa Cruz a couple of years ago.

"I worked in a warehouse for 10 years and realized how much waste we have, and I just wanted to break away from that lifestyle," Franco says. "I started thinking about how can I find another career that I could be proud of."

The teacher who taught the portion of the permaculture course on natural building caught his attention, and she was teaching another workshop in Portugal.

"I was ready to go on a big journey ... and I went ahead and just booked it," he says. "I just really got into it because I'm mechanically inclined and I love working with my hands."

During the 12-day workshop, Franco and 10 other students built an outdoor sauna. At the end of that workshop, his teacher was running another workshop in Portugal, so he followed her again. They built an outdoor kitchen with an oven attached to it. Then, there was a month-long workshop in Texas, where they built a 150-square-foot studio with a loft in it.

He's now attempting to start a cob building business on the Central Coast called Cobblers Delight.

"I wanted to learn as much as I could to build a big enough structure that someone could live in," Franco says. "If I can build my house for a fraction of the cost with good merit and good principles, then I would be happy."

Cob is similar to adobe, except it's not crafted into bricks. The structures are designed as monolithic pieces, a continuous piece built as one solid structure without seams or edges. Starting out at 12 inches or thicker at the bottom, the walls taper by 5 percent as they get taller. Those walls soak up the sun's energy during the day, Franco says, and that heat radiates into the house at night—and vice versa. Plus, the walls can be sculpted. Cob structures often have rounded edges or designs built into them.

"When it really comes down to it, the materials are dirt cheap, and all you really need is labor," Franco says. "Cob is so diverse, and if you want to add onto it, you can just chip off and add onto it."

A way of caring

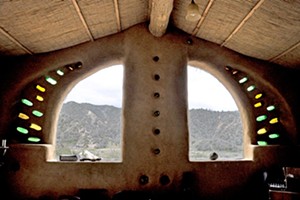

Quail Springs has beautiful buildings on its property, seemingly woven into the land from which they were built. Soft, rounded edges have suns and butterflies sculpted into them. Blue, green, and clear bottles are built into window spaces. Red branches of manzanita float in and out of the walls.

"The thing that I love about the material is that you just sculpt with it," Executive Director Setser says as she walks along one of the paths.

She points out the Magdalena, a space built by interns. Setser sits at a window seat coming out of the wall and leans back into the light. The point of this experiment is to figure out what works, Setser says, but it's also to give others the ability to do something similar if they choose.

Quail Springs is in the process of getting its structures permitted by Ventura County, which is the county most of its property happens to be on. She says the 450 acres also touch San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties.

"The point isn't just that we get our buildings permitted. The goal is so that other people who want to build out of earth can do so," Setser says. "Living light on the earth. ... The right to live in non-toxic buildings is fundamental."

People tend to think about permaculture as a farming technique, Rabin, who's in charge of Quail Springs' natural building, said. But really, it's a design system. You could take those principles and apply them to a business, Rabin said.

"A lot of it has to do with looking around your environment and how to grow something in that environment. ... And so natural building systems fit really smoothly into that," Rabin said. "We really design things really appropriate for a particular climate and a particular environment. ... If we were in Alaska, we would be building something different."

Because Quail Springs is in the high desert, there is only a minimal amount of things that can be grown. They try to grow as much food as possible with surface water. But, of course, they can't grow everything there, so Setser says they try to purchase as much from local farmers as possible, and they work with the Isla Vista Food Co-op in Santa Barbara. Eggs, milk, and meat are generated on-site. Goat and rabbit manure is composted with food waste and used in the garden.

Vegetable beds are sunken instead of raised and filled with compost to protect them from the wind. Poplar and locust trees regulate the nitrogen in the soil and block the wind and sun.

Permaculture is about earth care, people care, and fair share, Setser says, and Quail Springs is attempting to live by that mantra. It's not always easy. But it's worth it.

"We need places like this," she says. "There's a truth contained within it ... that touches people."

Reach Editor Camillia Lanham at [email protected].