Samantha Basulto was only a junior in high school when she had to let go of her first big dreams.

As a bright-eyed freshman who had never before struggled to make the honor roll, Basulto had imagined her future self running off to a four-year university immediately after high school graduation, leaving Santa Maria and all its hometown monotony temporarily behind–just as her older sister had years before.

But then Basulto was suddenly a junior, crying in front of the counselor who had once shared her four-year university vision.

A combination of personal issues and an especially difficult course load that year made school tough–and it showed. Her grades slipped, and Basulto said she ended the school year with a D in English, just below the C required to meet university entrance requirements.

"She just gave me a tissue and said, 'It's OK, you can go to Hancock,'" Basulto told the Sun just days after she graduated from Pioneer Valley High School without meeting her A-G requirements in June.

A-Gs are a specific set of coursework requirements California high school students must complete in order be accepted to schools within the UC and CSU systems. A-G courses are substantially different from those needed to simply graduate from high school. The courses require a higher final grade and are typically more difficult.

It's ultimately a student's responsibility to stay on track with the requirements, and while it can be easy to fall behind, catching back up is often no small task. Santa Maria Joint Union High School District schools don't offer many teacher-led summer school courses, and the district's only other program to help kids retake classes, On Track Credit Recovery (OTCR), is offered exclusively online.

So for most local high school students, many of whom come from families with little knowledge of the state's higher education system, a high school diploma is easier to obtain than a university acceptance letter. And while the district is working to improve its below average A-G completion rates, high school graduation is still the end-all goal.

Left behind

For Basulto, the timing just wasn't right.

When she was eventually able to retake her English class through the OTCR program, it was her senior year and already too late. OTCR courses are limited, and Basulto said the district's waitlist system prioritizes failing students, who may not graduate without OTCR, over students struggling to meet their A-Gs.

But even if Basulto had made it into OTCR earlier, she said she still probably wouldn't have been successful. After several days sitting in front of a computer in Pioneer Valley High School's library without an instructor leading the class, Basulto said she felt totally defeated.

"First of all, you failed it for a reason," Basulto told the Sun. "You didn't do well in that subject because you need extra help, you need someone to help and guide you. And then they just stick you in OTCR with a computer where you get no extra help? It's really difficult to do better."

She never finished the program.

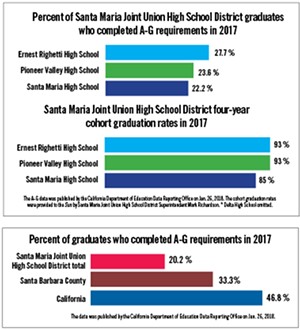

Basulto is now just one of the more than three-quarters of public high school graduates in Santa Maria who aren't even eligible to apply to a four-year university. In 2017, only about 20 percent of Santa Maria Joint Union High School District grads met their A-G requirements, according to data compiled by the California Department of Education. That means only 360 of the district's 1,778 grads were eligible to apply to CSUs and UCs last year.

The district's A-G completion rates have historically been significantly lower than those of Santa Barbara County and California as a whole, according to California Department of Education data. In 2017, about 33 percent of the county's graduates completed A-Gs, as did about 47 percent of the state's.

It's an issue that many local high school students feel hasn't been addressed, and although Basulto said she felt abandoned by her high school education system, the experience inspired her and others like her to take action.

Basulto and several other students involved with Future Leaders of America hosted a community forum on A-G requirements at the Veterans' Memorial Center on May 9, after spending nearly eight months researching university entrance requirements and how they impact local students.

At the forum, 10 Santa Maria students shared personal stories that closely echoed Basulto's: they were meeting their A-G requirements until, for whatever reasons, they weren't, and then it was nearly impossible to get back in the game. Most kids said their counselors told them at some point to "just focus on graduating." Some said they didn't even know what A-Gs were until they got to high school.

"They don't care," Basulto told the Sun in June. "They just want to focus on us graduating when it's our dream to go straight to a four-year university."

At the forum in May, students posed a solution: align high school graduation and university entrance requirements.

It's a big idea that would take time to implement. In order to graduate high school, students would have to take additional courses–two years of foreign language rather than the one currently required to graduate, for instance, and three years of math rather than two–and those courses would have to be UC and CSU approved. If graduation and A-G requirements were truly aligned, students would also have to score all Cs or better to graduate, instead of the Ds that are currently considered diploma worthy.

It sounds daunting, Basulto said, but she and other students with Future Leaders of America think higher expectations would garner better results.

"Realistically, in our district we can graduate with a 1.0 grade point average, getting straight Ds all through high school," Basulto said at the Future Leaders of America office in June, where several members gathered post-graduation to discuss A-Gs. "That is extremely low, that is really sad, and I'm pretty sure all of us here can agree that we've heard our peers say, 'Oh, it's OK, I can graduate with a D.

"So if the standards were C, we'd try harder," she said. "We don't push ourselves because the standards are so low, because we know it's OK to get a D."

It's the safety net that Santa Maria's cohort of Future Leaders of America identified as the system's leading problem, and they aren't the first to want it cut.

'Raising the bar'

The Oxnard Union High School District voted to closely align its graduation requirements with university entrance requirements in mid-May, after a group of unwavering high school students with Future Leaders of America spent years pushing for the change.

The district's multi-tiered alignment plan will be fully implemented by 2024, according to Oxnard Union Superintendent Penelope DeLeon, who said current sixth graders will be the first high school class in Oxnard held to higher standards.

Graduation requirements won't exactly mirror A-Gs–students will still be able to graduate with Ds, and Career Technical Education pathways will be offered to students who aren't interested in attending four-year universities.

But DeLeon said each of the district's courses will be UC and CSU approved within the next year, essentially eliminating any non-college-prep pathways that currently exist. College-prep, whether a student wants to attend a two- or four-year school after high school, will be Oxnard Union's "default" curriculum, DeLeon said.

To achieve that, she said district officials spent the last two years reworking and rewriting 90 courses, all of which were submitted to the UC and CSU systems and are currently awaiting approval.

Oxnard Union is also working closely with its feeder districts, which oversee elementary and junior high schools, to provide support services that will ensure future high school students are fully prepared for the new standards.

"The idea is that we want every single student to leave our district with multiple post-secondary options," DeLeon said. "So we believe that raising the bar is actually more of a social and economic movement in this community than it is an education movement."

The issue is systemic, according to Eder Gaona-Macedo, executive director of Future Leaders of America. Gaona-Macedo, who worked with Oxnard students on A-G alignment and is working with Santa Maria students now, said university entrance requirements are just a small part of the broader issue: creating a college-going culture for students who may not otherwise take that route.

Many high school students in Oxnard and Santa Maria, he said, don't come from college-educated families. And without the help of someone who has successfully made it through the system–someone who knows about entrance requirements, applications, and financial aid–it can be difficult for kids to stay on path to four-year universities.

"I came here to the states undocumented," Gaona-Macedo told the Sun, "so my mom was born in Mexico, and she doesn't necessarily understand the American education system."

To his mom, Gaona-Macedo said, success just meant graduating high school. It meant walking in a gown, smiling for the camera, and getting that diploma.

"So she didn't know the difference between graduating and completing these rigorous courses, the A-Gs," he said.

A lot of current students live in similar situations, Gaona-Macedo said, and it can be easy to fall behind early on when college is anything less than an inevitability. While some students hear all about higher-education from an early age, others don't until teachers and counselors discuss it in high school, when it's often already too late to jump on the university track.

Gaona-Macedo said part of creating a true community-wide college-going culture is setting that high college expectation for all students from a young age.

"There have been countless studies done that show if you set expectations high for students, they're going to meet them," he said. "And if you set them low, well, that's what they're going to achieve."

Searching for solutions

Despite the "hubbub" surrounding Oxnard Union School District's coming changes, Santa Maria Joint Union High School District Superintendent Mark Richardson said alignment is unlikely to make its debut in Santa Maria anytime soon.

The Santa Maria Joint Union High School District's goal is to provide options for all students, Richardson said, regardless of whether or not they'd like to attend a university right after high school.

"We have kids who aren't interested in going on to a four-year university," Richardson said. "We have kids who are interested in going out and doing something different with their lives, and we certainly want to make sure they have the high school diploma to do it."

The district, he said, offers a vast breadth of Career Technical Education pathways, and while many of those do not lead directly to four-year schools, they do give kids the skills and certifications necessary to go out and get high wage, skilled labor jobs.

And for many of the district's students, Richardson said heading straight to a four-year university after high school simply isn't the best option, and it's certainly not the only way to get to a UC or CSU.

For some kids, attending a school like Allan Hancock College, which offers a free first year of tuition to local high school graduates, then transferring out to a four-year is really the only viable option financially. And for others, Richardson said starting at a community college is the best option academically.

"To have the expectation that a student who comes to us as a freshman and is illiterate in [his] home language and we're teaching [him] English," Richardson said, "and somehow we're going to be able, in the course of four years, to teach a student English and get [him] to qualify for four-year college admission through the UC system by taking this advanced set of coursework? I think it's unrealistic to do that."

Still, Richardson said the district's A-G completion rates are admittedly low, and he'd like to see those numbers improve within the next few years. It's something Richardson said he and other district officials have been working toward for years, through increased counseling services and the implementation of various college-readiness programs, including Achievement Via Individual Determination (AVID).

AVID, Richardson said, is a program the district launched four years ago that is designed to help students develop the skills they'll need to attend universities. It helps bridge the gap between high school and college for kids who may not have college-educated parents or family members to act as mentors.

Of the 129 Santa Maria, Righetti, and Pioneer Valley high school students who completed the AVID program this year, 119 were accepted to the UC or CSU systems, according to a district press release from May. Richardson said he expects that program to continue producing successful results.

Several of the district's other attempts to break down college-going barriers have also proven triumphant. Using funding from a California Academic Partnership Program (CAPP) grant that was awarded to Righetti High School five years ago, CAPP Coordinator LeeAnne Del Rio said district officials identified several ways to increase student access to universities, and instituted eight of them throughout the grant's lifetime.

The CAPP grant, Del Rio said, put counselors from Hancock and UC Santa Barbara on each of the district's high school campuses to lead the Early Academic Outreach Program, which helps further prepare students for college and the workforce.

The funding also allowed Santa Maria Joint Union High School District officials to thoroughly improve counseling outreach and the Hancock credit transfer and placement assessment systems, which Del Rio said students previously found to be confusing and inconvenient.

Two particularly successful CAPP programs–Summer Jump Start and Summer Geometry–bring students with lower-level math, science, and reading skills up to speed, before the damage is irreversible.

Summer Jump Start, Del Rio said, is designed to get junior high schoolers prepared for high school courses, while Summer Geometry allows lower-level math students to complete an entire year of geometry in six weeks of summer. For students who may need to retake an entire year of math, that accelerated class can make a big difference.

In 2014 and 2015, Del Rio said more than 80 percent of students who completed Summer Geometry met their A-G math requirements. In 2016, Del Rio said 100 percent met their A-Gs in math.

But the CAPP funding ended this year, and Del Rio said it can be challenging to recruit teachers for summer school, when they are paid less than their usual salaries. Without teachers to lead the Summer Geometry and Summer Jump Start programs, neither are currently offered.

Funding is always an issue for the district and its students, but motivation never runs low among those involved with Future Leaders of America.

Basulto, now 17 and on her way to Hancock in the fall, said she hopes future students continue to push for alignment, the key to creating a real college-going culture.

"The main reason for me is that if you align A-G requirements with graduation requirements," Basulto said, "that means every single person who graduates from our district will have the opportunity to go straight to a four-year."

And students, she said, deserve to have a choice.