A few curious neighbors watched as carpenters pieced together the wooden skeleton of a 2,138-square-foot house on the corner of South Bradley Road in Santa Maria’s Sunrise Hills neighborhood on May 8.

The finished product would one day include a spacious kitchen, lower and upper level living rooms, three bedrooms, two and a half bathrooms, and a two-car garage, according to longtime real estate agent and developer Gary Crabtree. The finishing touch: a beautiful view of the distant mountains stretching out past Highway 101.

But where backyard grass would normally grow sat the beginnings of Santa Maria’s first ever newly constructed accessory dwelling unit—a miniature version of the home situated directly beside it.

“A lot of people don’t even know what an accessory dwelling unit is,” Crabtree said, motioning toward the smaller of the two structures sitting on his residential lot. “I had people come over who thought I was building a big garage or a workshop next door.”

But with two bedrooms, two baths, a kitchen, and garage, Crabtree said the 1,000-square-foot accessory dwelling unit will likely be used to house another individual or family—people who otherwise might not find housing in the area’s ever tightening market.

The city has issued 10 building permits for accessory dwelling units since the Santa Maria City Council reluctantly adopted an ordinance allowing for the use and construction of the units in residential neighborhoods at a meeting in December 2017. Roughly 20 other applications are still in the city’s review process, according to Santa Maria Planning Manager Ryan Hostetter.

While Hostetter said it’s still unclear exactly how each accessory dwelling unit will be used once built, city and state officials say the units—which could benefit both homeowners and renters—may become part of a greater solution to California’s growing housing crisis.

Crabtree, who hopes to build more houses and accessory dwelling units in the near future, said he agrees.

“I think it’s important to know that it’s going to help part of the housing crunch,” Crabtree said. “It’s just one more step in the right direction.”

Accessories to housing

Although the Santa Maria City Council voted unanimously in December 2017 to allow accessory dwelling units in residential neighborhoods, council members didn’t have much choice in the matter.

Several state bills requiring cities and counties to adopt regulations allowing accessory dwelling units were signed into law in September 2016, according to a city staff report. The bills were passed in an effort to increase the state’s rental unit inventory.

The majority of Californian renters—more than 3 million households—pay more than 30 percent of their income toward rent, and nearly one-third—more than 1.5 million households—pay more than 50 percent of their income toward rent.

Overall homeownership rates are at their lowest since the 1940s.

California’s 39 million people live in 13 million households across 58 counties and 482 cities.

The statewide median single-family home sale price was $526,580 as of August 2016. As of first quarter of 2016, the California Association of Realtors estimates that only 34 percent of households in California can afford to purchase the median priced home in the state.

Santa Barbara County’s median existing single-family home sale price was $430,000 to $824,000 as of August 2016. Forty-three percent of all Californian households are lower-income.

Twenty-nine percent of owner households and 61 percent of renter households in California are lower-income.

“[Accessory dwelling units] are generally regarded as an effective way to increase housing options while minimizing changes in neighborhood character or creating additional sprawl,” the staff report reads. “They can effectively provide affordable housing for renters, a source of income for homeowners, and a housing source for multi-generational households, including extended families, as well as seniors, college students, and others.”

Through Santa Maria Ordinance No. 2017-21, accessory dwelling units—also commonly called granny flats or in-law apartments—can be created through the conversion of existing living space in a single-family home, through an addition to an existing home, or by constructing an entirely new detached structure.

Crabtree chose the third route, and while he plans to build houses and detached accessory dwelling units on six lots in Santa Maria from the ground up, he said he’s heard from many fellow homeowners who plan to simply convert their garages into dwelling units.

“With the new laws, they’re allowed to convert those into residential units, whereas with the old laws you were not because they were too close to the property line,” Crabtree said. “So I think you’ll start to see a lot more of that type of conversion.”

Accessory dwelling units are seemingly beneficial to everyone—the lower permit costs allow developers to build the units for little extra cash, homeowners could rent them out and thus supplement their own mortgage payments with a new source of income, and renters have more housing to choose from.

Families could also benefit, Crabtree said. Aging seniors or struggling college students could live close but separate from their families on the same residential lot. Crabtree said his own children have returned home several times, and if he had room for an accessory dwelling unit on his own property, he said he’d house them there.

Still, some City Council and community members have concerns about the negative impacts accessory dwelling units could have on residential neighborhoods.

At a City Council meeting in December 2017, Councilmember Michael Moats said he thought the state laws requiring local jurisdictions to allow granny flats were horrible, and he requested as many restrictions on the units as possible. Councilmember Mike Cordero said it could be difficult to regulate the unintended consequences of accessory dwelling units.

Overcrowding and a lack of available parking spaces were the City Council’s major worries, Crabtree said.

“It’s always the fear of the unknown,” he said. “That’s always the mentality: ‘It’s a good idea, but put it somewhere else.’”

Supplying the demand

People don’t like change, according to Community Development Director Chuen Ng, who said that disposition has always been an issue when regulating development in Santa Maria’s residential neighborhoods.

“But I understand that because people buy a house, it costs a ton, and they have expectations of how their neighborhoods should be,” Ng said. “And they want things to stay a certain way.”

The inclusion of accessory dwelling units in single-family neighborhoods will increase the number of people living in those areas, and thus the number of cars parked on surrounding streets. But Ng said it likely won’t be too dramatic a shift.

In an effort to further address any possible disruptions, Ng said the city’s ordinance includes a deed restriction: Property owners are required to live on site.

The requirement prevents property owners from renting out both their accessory dwelling units and homes—which Ng said could create a duplex situation—while allowing for accountability. If neighbors have any issues with granny flat renters, property owners are on-site and easily accessible.

Even if the City Council could have continued its prohibition of accessory dwelling units in residential neighborhoods, Ng said there aren’t a lot of other simple solutions to California’s housing problem.

The state’s overall homeownership rates are at their lowest since the 1940s, according to “California’s Housing Future: Challenges and Opportunities,” a statewide housing assessment published in January 2017. Only New York and Nevada have lower homeownership rates.

The study also found that while California’s median cost of rent increased by more than 20 percent from 2000 to 2013, median income for renters decreased by almost 10 percent in the same time frame.

Ng said the housing crisis is an example of what can happen when supply doesn’t keep up with demand.

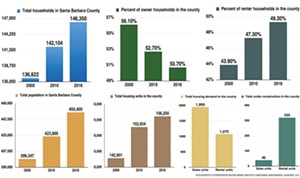

While California produced an average of less than 80,000 new homes each year for the last decade, it’s estimated that 180,000 homes are needed annually. And Santa Barbara County is struggling with the same issue, according to the Comprehensive Housing Market Analysis of the Santa Maria-Santa Barbara Housing Market Area published in August 2016.

The assessment estimated that Santa Barbara County would need to build nearly 2,000 sales units and more than 1,000 rental units to achieve a balanced market by Aug. 1, 2019. As of Aug. 1, 2016, only 40 sales units and 320 rental units were under construction.

“We just don’t have enough supply,” Ng said. “So from a planning perspective, if we plan for more housing, we hope that will kind of ease the demand, and that anyone looking for a place to live can do so more easily.”

While adding to the housing supply would, in theory, decrease demand and thus the costs of renting or buying a home, Ng said Santa Maria is running out of space.

Houses, businesses, and schools fill up nearly every empty lot and butt up against each corner of Santa Maria’s city limits. Ng pulled up an aerial map of Santa Maria on his computer and hovered the cursor over a single, empty square that sat among a sea of buildings.

It’s one of the last large, empty parcels of land remaining. The land between South Blosser, West Stowell, and West Battles roads could accomodate roughly 1,000 housing units, Ng said. That’s potentially 3,000 people.

While the land is currently being used for agriculture, Ng said the city is working with its owner on development plans for housing, businesses, a park, and a school.

Still, Ng said that piece of land will only satisity Santa Maria’s population for a year or two, and expanding city limits to make more space for housing is a strenuous process that could take years.

Accessory dwelling units, on the other hand, can be built on existing land. They’re cheaper than houses or apartments to build, and don’t need separate water and gas meters.

“They can be a good form of affordable housing,” Ng said.

And if the Central Coast needs anything, it’s more affordable housing.

Bearing the burden

Sarah Cale moved from Nevada to California nearly 10 years ago for the state’s accessibility to disability services. Cale is deaf and has a disease that often causes extreme dizziness—sometimes it’s so bad that she can’t even walk.

In Nevada, Cale said it was nearly impossible to find the disability services she so often needs, an issue she rarely faces in California.

But her move to California brought a different challenge: finding an apartment she could afford with a disability income. Cale said her illness, which often lands her in the emergency room for days a time, makes it impossible to work.

“So unfortunately, as much as I would love to work—I have degrees for deaf studies that would allow me to teach sign language in college—I can’t do it because there is no predicting whether or not I’ll be able to get up and if the vertigo is going to attack me or not,” Cale said.

After Cale applied for affordable and low-income housing developments in Sacramento, San Luis Obispo, Redding, Riverside, San Diego, Ventura, Santa Barbara, and Carpinteria without luck, she moved in with a family friend in Buellton while she continued to apply for more permanent places on the Central Coast.

When that living situation ended, the only almost affordable place she could find was a converted garage in Guadalupe.

“That didn’t even have a kitchen, and I was paying over half what I get from my disability check for rent,” Cale said “And they gave me a discount too because they felt bad for me.”

She eventually discovered Peoples’ Self-Help Housing, a nonprofit with roughly 1,800 affordable housing units on the Central Coast. Cale said she applied to several Peoples’ Self-Help developments in the area and was put on a lengthy wait-list—she was told to expect a five-year wait.

Due to a series of fortunate events, including her willingness to take a studio apartment, Cale said she moved from No. 40 to No. 1 on the wait-list after only a year. She moved into a 400-square-foot studio apartment at Valentine Court in Santa Maria, a Peoples’ Self-Help development for low-income, disabled individuals.

Cale said she’s lived there for three years and doesn’t plan on leaving any time soon.

“Normally once people get in they don’t want to leave,” Cale said, “because where else are they going to go?”

As defined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, housing is considered affordable when a person pays no more than 30 percent of his or her income toward housing costs, including utilities.

But the majority of California renters pay far more than 30 percent of their income toward rent, according to “California’s Housing Future: Challenges and Opportunities.” Nearly one-third of the state’s renters pay more than 50 percent of their income toward rent, according to the assessment, and 43 percent of all Californian households are considered low-income.

That’s why the wait-list at affordable and low-income housing developments are so long, according to People’s Self-Help President John Fowler, who said there are wait-lists of hundreds of applicants long at each of the 51 organizations’ locations that currently exist.

“It’s always taken a long time to produce and there has always been a demand, but nothing like we’re seeing today,” Fowler said. “The market has just really pushed more and more people into poverty and into needing affordable housing.”

Development and funding approval are challenging processes that often take years, Fowler said, but those processes need to be streamlined to keep pace with the increasing need for housing.

Fowler said multiple laws addressing development and housing passed at the state level in the last few years, including the accessory dwelling unit bills, and he said he’s glad to see the state working to find solutions.

“It used to just be the poor people and the people who don’t make much money,” Fowler said. “Now all of a sudden you could make area median income and have a housing problem.

“So I think people are getting the message that it’s a crisis,” he added. “And it’s a crisis for everybody.”

Contact Staff Writer Kasey Bubnash at [email protected].