The Madonna Inn, a historic spot right off of U.S. Highway 101 in San Luis Obispo, is well known for its amazing cakes. What isn’t as well known is that the inn’s restaurant and bakery leaves its doors unlocked even after closing time, so workers and local law enforcement agents can come and go, explained co-owner and general manager Connie Pearce.

“For the majority of the people, they appreciate that late at night, if they have to run in and use the restroom, there is a safe and comfortable place to pop in and pop out,” she said. “And that’s what we’re all about.”

That offer of comfort, safety, and trust was taken advantage of on the evening of Feb. 8, when a then-unidentified man walked into the restaurant, went behind the counter, and absconded with a cake. The baked good in question just so happened to be a special order with personalized writing in icing.

“It’s one thing when they are just taking something that is not theirs,” Pearce said, “but if it’s a special order for someone else, it causes hardship on several people.”

The security camera that faces the entrance of the Madonna Inn captured footage of the cake-napping, and Pearce posted a video clip to her Facebook.com profile page the next day.

She didn’t expect what came next.

“It was pretty grand and rapid fire,” she said. “I was just amazed by how many people shared the video; it was absolutely insane. It got shared 519 times.”

By the end of the night on Feb. 9, Pearce had the suspected thief’s name and knew he lived in Morro Bay and other details about his life. She notified authorities of the alleged burglar’s name and location. Reports indicate that officers went to the man’s home only for him to flee out the back window. A couple of days later, someone connected to the suspect paid for the cake during regular business hours at the inn.

“I was going to press charges then, but in the end … I didn’t want to cause the guy harm,” Pearce said. “Maybe this will make him change his life.”

What, at the time, might have seemed like an innocuous theft to the alleged perpetrator quickly became a nightmare. Everyone on the social media platform was talking about the crime, and those who knew him certainly recognized him in the video. Furthermore, his name is posted in several news stories online, along with the viral video, for the entire world to see.

“This was one of the things I was trying to get out to the general public,” Pearce said. “If there is anyone who wants to come and do damage to us … I do have cameras. And if they do something to harm us, I’m not going to sit back and let it happen.”

A new era of investigation

Within hours of the Boston Marathon bombings of April 15 last year, a large-scale vigilante investigation began on such websites as Reddit.com. Users scoured photographs taken at the event before the improvised bombs detonated.

Though mobs of skeptics can appoint themselves investigators via the Internet, professional detectives are still the ones who actually get the work done in working to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Though the Internet has changed much in our age, it hasn’t altered the basics of investigation, explained Lt. Kelly Moore with the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Department.

“The success or failure of our investigations really come down to the success or failure of our investigators,” Moore said. “Generally speaking, you don’t have one piece of evidence that is going to hang somebody; it’s usually a bunch of little pieces of evidence that come together.”

Current technology can help investigators piece together an investigation in a variety of ways. Most smart phones these days are equipped with GPS and location data, and detectives can get GPS information with a search warrant, if it’s needed in an investigation.

“We don’t have the ability to track people and open up the camera on their phone, but there are people who think we can,” Moore said. “Literally, the rights of privacy extend to phones and homes, so the Fourth Amendment applies. So if we want to get into that stuff and work with a provider, we need a search warrant. They won’t give us anything without a search warrant.”

Search warrants can help law enforcement verify such details as the location of a cell phone at a certain time, or whether a text or call was made at a certain time—a technique that’s become the bane of distracted drivers. But much that could help in an investigation is open not just for detectives, but also for anybody looking.

“Generally speaking, and I don’t want to be giving away our techniques, but there aren’t really any secrets,” Moore said. “Anything you post on the Internet is on the Internet.”

Many users fail to recognize that what they put on social media platforms is public as soon as they publish it. Tweets, Facebook posts, Instagram photos, and YouTube videos are all essentially public record, unless some specific changes are made to a profile. Therefore, just about anything you post could be considered evidence if you end up being investigated for something.

“One of my concerns right now—with all the [Edward] Snowden and NSA stuff—people think that we are just sitting around looking on the Internet and going through people’s Facebook and Instagram accounts and looking for things they are doing wrong,” Moore said. “We don’t do that. We can’t do that. We can’t just start randomly looking, but if something points us somewhere, we can use those tools that are available to us.”

Logging real consequences

Anthony Murillo of Orcutt was in court briefly March 12 for a hearing that was scheduled to continue on March 19. Murillo is a friend of Shane Villalpando, the young man currently serving a jail sentence for unlawful sex with a minor.

In an apparent act of solidarity with his incarcerated friend, Murillo had recorded a rap song.

“Moment for Life Remix” is one second shy of two minutes long, and begins with a lament set to a synthesized baseline and electronic drums. It’s not until the last 30 seconds of the song that he addresses Villalpando’s victims, calling them various slurs and finally naming both of them. The recording ends with the lines: “I said go and get the Feds, cuz you’re going to end up dead/You’ll be laying on the bed, because I’m coming for your head bitch!”

That last line is delivered just as the computerized accompaniment cuts out, Murillo’s voice ringing out with the confidence most rappers take pride in. It’s obvious that a lot of work went into producing the song: Lyrics had to be written, beats and music produced and acquired, recording and audio mastering all had to take place before Murillo posted the song to the Internet. Once online, the song entered an echo chamber, which would come back to haunt the rapper in court.

Murillo posted his song on ReverbNation.com, a website that combines a sophisticated social media platform with media sharing specifically for musicians. Users can coordinate with venues, post recordings, and make posts to other social media platforms. When Murillo uploaded his song, it appeared on all his social media accounts, including Facebook.com, where it was seen by one of Villalpando’s victims.

“At first when I heard the song, I was traumatized and scared,” Delaney Henderson told the Sun in an email, “that they are still trying after all this time to hurt me and the other victim.”

Henderson has turned 18 since Villalpando’s conviction, and, like the other victim, was ultimately forced to move out of the area due to the amount of harassment she endured. Though the courts outlaw naming the minor victim of a crime, which is one of the felony charges Murillo is now facing, Henderson still found herself in a community of people who were talking about her behind closed doors.

“The other parts of the song are words I have heard before; to be honest, I’ve been called worse,” she said.

Murillo appeared in court on March 12 flanked by a group of friends, as well as a smaller group of assuring adults. His lawyer is arguing that the song is art, and not a direct threat of violence intended toward anyone else, and should therefore be protected under the First Amendment. Besides the naming of the victims, the seriousness of the threat will be a big deciding factor in whether Murillo is convicted and serves any kind of sentence.

“An online threat is like any other threat,” the Sheriff’s Department’s Moore explained. “It really depends on the contents, the context, and the specificity of the threat.”

Local law enforcement agents are mandated to investigate several types of crimes, including sexual assault, child abuse or molestation, elder abuse, school threats, or threats to investigators, judges, witnesses, or victims. In the case of threats, Moore explained, investigators assume they’re valid unless it can be determined they’re not serious.

“If I said, ‘I’m going to kill that guy,’ would that be taken seriously?” Moore said. “It may or may not be, depending on the context of the conversation. But it elevates the validity and seriousness of the threat if you say, ‘I’m going to hunt you down, I know where you live, I have an AR-15, and I’m going to shoot you when you get in your car.’ That shows much more thought and seriousness.”

In the case of an online threat, which is considered just as valid as any other threat, the seriousness or the ability of the user to accomplish the threat comes into question. In the preliminary trial, Murillo’s attorney tried to establish that the young man is an artist, not a dangerous criminal.

“That’s the way that people have to look at this; it isn’t that we can just press a button and have all the incriminating video and postings,” Moore said. “It’s not usually one piece of information that incriminates somebody; it’s usually a whole bunch of things that they do.”

Not long after posting his song, Murillo deleted it, but not before it was downloaded by several people and submitted as evidence to local law enforcement. His ReverbNation, YouTube, and Facebook pages are still up and running. The Facebook page even includes the original posts of “Moment for Life Remix” made in September of last year, though a different song streams from the link now. Deleting files or activity from social media sites removes the information from public view, so anyone savvy with a Google search shouldn’t be able to find the incriminating post, but that alone doesn’t stop a police investigation.

“Once you put something on the Internet, there are ways to find out where it came from,” Moore said. “We have always got cooperation from our service providers. They don’t give us anything without a warrant, and they want to protect the privacy as much as they can, but they understand when a judge says they need to give it to us, so they do.”

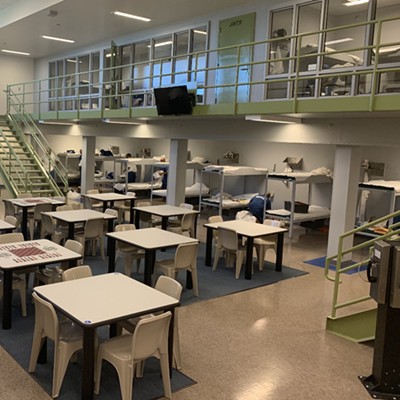

Using warrants to acquire hidden or deleted activity online is one way law enforcement gains evidence. During Murillo’s preliminary hearing on Feb. 19, evidence of his intent was shared in the form of a conversation between Murillo and Villalpando that was recorded during a visit Murillo made to his friend in jail. Another piece of evidence introduced was a photo of Murillo posing with a shotgun. It all serves as evidence.

“We use each little piece of information like a brick, and the goal is to build a wall,” Moore said. “As you get started, it doesn’t look like a wall, but a pile of bricks, but the more you build it, and the more bricks you get, it starts to resemble a wall.”

Some people might not be aware that they’re essentially helping investigators build a case against themselves. Certain posts might seem innocuous or silly when they’re uploaded, but they may later help paint a picture.

Murillo has a profile on Ask.fm that describes him as a hip-hop artist from the Central Coast, and also links to the Facebook page where he shared “Moment for Life Remix.” The profile can be found with a simple Google search of Murillo’s name and is viewable to anyone with access to the Internet. A list of questions trails down the profile page. The third down, dating from around the time Murillo posted “Moment for Life Remix,” asks, “What’s one thing everyone should do in their lifetime?” The reply is simply two words: “Kill someone.”

Contact Arts Editor Joe Payne at [email protected].